La guerra y los medios

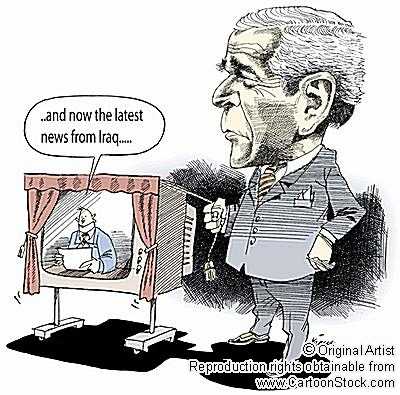

Mientras se discute el cómo EE.UU. saldrá de Irak y cómo evitará que la guerra civil -ya en proceso- termine por dividir a ese país, el Columbia Journalism Review dedica su último número a analizar la cobertura de los tres años de invasión. A pesar de las virtudes de la prensa estadounidense, cuando se entra en el detalle, la guerras parecen su mayor debilidad. Sólo un dato, mientras EE.UU. era aliado de Irak en los ochenta, los medios escondieron buena parte de las atrocidades de Sadam Hussein en contra de los iraníes y los kurdos. Pero el año de invasión, los mismos argumentos que callaron fueron usados para justificar el ingreso de tropas y el derrocamiento de Hussein. De esta incoherencia no se escapó ni el New Yorker. A veces las culpas que caen sobre el periodismo parecen muy justificadas. Esta es la editorial del especial del CJR y más abajo están los links a los textos principales de la publicación.

In the middle of 2003, not long after President Bush landed on the USS Abraham Lincoln in May to tell the world that “major combat operations in Iraq have ended,” Time Books came out with a glossy hardback titled 21 Days to Baghdad — The Inside Story of How America Won the War Against Iraq. The book concludes with a shot of the president on the Lincoln in that snug flight suit. Although it includes one horrific shot of Ali Ismail Abbas, the twelve-year-old Baghdad boy who lost both arms and his family to a U.S. missile in March, the book is an oddly sanitized thing, the portrayal of a tidy and limited little war. The triumphant text tells us that the V-J Day moment in Iraq arrived “on April 9, when a U.S. team tied a chain to a statue of Saddam in Baghdad’s Paradise Square and, with a couple of hefty yanks, pulled it from its pedestal.”

The book is a time capsule in a way and, though it is not a very old one, it has a whiff of rot. It is an embarrassment, but it’s also a useful reminder of how reportorial curiosity can surrender to patriotic stagecraft, and in turn, how such stagecraft can shield policy from inquiry at critical moments. The book feels both innocent and cynical.

For this special forty-fifth anniversary issue of the Columbia Journalism Review we have constructed a different kind of history of the war, an oral history told through the voices of many of the journalists who have covered it. We interviewed forty-five reporters, photographers, translators, and stringers, and gathered war photos, too, many of them previously unpublished in the U.S. Our starting point is the fall of Baghdad, and the reader will see that even before Saddam’s statue hit the ground journalists were picking up signals that America’s time in Iraq would be complex, confusing, and worse.

The oral history starts on page fourteen. It has several interlaced story lines. One is a record of how western journalists woke up to the growing chasms in Iraq between Americans and Iraqis, between soldiers and civilians, between the Green Zone and the rest of the country, and to the rifts among Iraqis themselves. The history is also an account of the impediments — practical, political, professional — that journalists have faced while covering Iraq, and how they have overcome those impediments or failed to do so.

As we read transcripts of our interviews another story line emerged: how individual journalists began to appreciate the deep danger they were in as the occupation wore on and the insurgency took hold, and how they dealt with it. You can’t read this history without admiring the skill and guts that these journalists bring to the job, their stubborn effort to get the story right despite the obstacles. Or without appreciating the fact that the coverage of the war and the course of the war are somehow intertwined.

We were also struck here at cjr by the passion and expertise of these particular voices — and also by the fact that the conventions and traditions of journalism sometimes muffle this power and passion in their work. Many of these people have been in Iraq longer than some of our soldiers and diplomats. We need to hear them. They know things.

http://www.cjr.org/issues/2006/3/schulman.asp

www.cjr.org/issues/2006/2/McLeary.asp

www.cjr.org/issues/2004/6/fassihi-baghdad.asp

www.cjr.org/issues/2004/6/matloff-memory.asp

www.cjr.org/issues/2004/4/mccollam-list.asp

Etiquetas: periodismo

1 Comentarios:

cep udp 07

Publicar un comentario

Suscribirse a Comentarios de la entrada [Atom]

<< Página Principal